A distinction with petty origins, for people who have trouble explaining how they run their games. Rulings and rules, together at last.

In a grand-standing tradition of using your blog as a platform to win arguments with people who have moved on ages ago, and will almost certainly not recognize themselves in the post even if they read it, this one is a little more specific than most. It's not about any one game, but rather a subset of games, their rules, and their philosophy around them. It's also not meant to change anyone's perspective or redefine existing terminology, just to (hopefully) give people a new term to help avoid spending an hour in a non-argument before realizing that you and the other guy have been using two different meanings of the same term.

Not that I'm bitter or anything.

This is a short post by Orbital Crypt standards, which is why I'm padding it out with pointless observations such as this one, but I hope that it'll be a useful one. Now let's get to the main point first, before we devolve into overthinking.

|

| We're well known for the level of our discourse, around here. |

What is a Palette RPG?

I define a Palette RPG as a game that is fundamentally open to choosing when to use (or not use) the rules, as the GM sees fit. A game that relies heavily on GM arbitration, uses fictional positioning to determine the stakes of a situation (rather than more detailed or "hard" mechanics), and doesn't have a "guiding" game structure is the ideal Palette RPG. A Palette RPG should have a solid and complete set of rules, and those rules should act as the baseline for assumptions about doing things in the game; but those rules are not hard, nor fast, and the game will not break down if any of the systems are ignored during play.

I use the term "Palette" because I liken the idea to an artist's actual, physical palette: you encounter a situation that requires resolution, and you pick what "colors" (rules or subsystems), if any, would be appropriate to "fill in" the situation of the game.

So, a Toolbox RPG?

See, this is why I wrote this in the first place. "Toolbox" is one of those terms that has been thrown around so much, and with so many different assumptions behind it, that I feel it's no longer useful. Here's a non-exhaustive list of the stuff that I've seen described as a Toolbox:

- Games that feature many optional rules and systems that let you customize your experience,

- Universal systems such as GURPS, which require the GM to assemble their own game from a provided list of subsystems,

- Universal systems in general,

- Games with a large collection of tables and mostly-standalone subsystems easily used in other games,

- Generic non-system books that do the same as the above,

- Games that conform to my definition of Palette RPG to varying degrees,

- Games that literally contain some variation of the phrase "GM tools" as a heading (no, I am not kidding).

For the record, I'd personally probably #4 is closest to my mental image of a toolbox game, but that's besides the point. I'm coining the phrase because I want people to know what I mean when I say that a game is a Palette RPG: A game that provides freedom while still having a solid core to rely on.

|

| All games contain "tools", but it feels weird to define a game as Having Tools. |

...Isn't this just Every TTRPG Ever?

Well.

Here's the thing: I've read a lot of rulebooks over my spaceborne lifetime, because I'm the particular flavor of nut that just enjoys reading rulebooks. I also always read the author's introduction, the obligatory "What is a roleplaying game" section, and whatever else lies between the table of contents and the main body of text that constitutes The Actual Game. I do this because I want to understand what the author thinks, and why: what do they consider to be a roleplaying game? Why did they make one? What do they want me to know going into it? It's all very interesting.

Probably the single most common bit, sitting at the beginning of almost every rulebook I've gotten my hands on, is some variant of the famous "rule zero" or "golden rule", paraphrased in the following:

The rules in this book are not the final word. If there's something you don't like, that isn't fun, or you think doesn't work - change it! This book is a set of tools, a toolbox if you will; and it's up to you to decide what you want it to be.

This is, technically, true for all non-digital games; whether it's a TTRPG, a board game or a sport, a game is a set of rules that we collectively agree on, to create a shared mental space where play can happen; and throughout history people have changed rules to their liking, which is why many classic and popular games have house rules or regional variants. Where this idea falls flat for many games, however, is their internal construction: the more complex or interconnected a game's overall systems are, the harder it is to make any core changes without fundamentally altering the entire thing. This is where the GM comes in for a Palette RPG: You don't change the rules, you choose the moment where it's appropriate to not apply them to make a more satisfying game.

That doesn't mean that some elements of games cannot be changed, modified, added or removed; even the most "hard-coded" games are open to a degree of customization and addition of "homebrew" stuff. In fact, many games thrive on the fact that they provide a solid, immovable base with discrete, well-defined game object types, that one can easily add their own game objects to. And that's great.

But I think that it's important to distinguish between games that "can be customized", and games that I'd consider Palette games. I'll try to clarify this with an example.

|

| Bet you didn't see this one coming. |

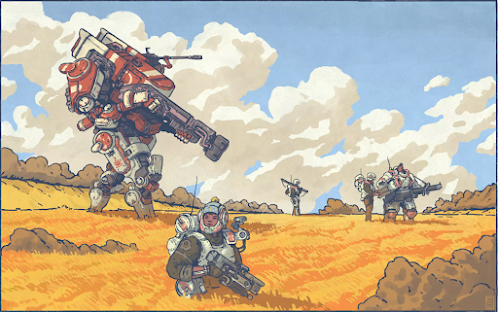

Lancer: A Game That I Quite Like, That is absolutely not a Palette Game

If you haven't heard about the excellent Mecha RPG Lancer, I strongly suggest you take a few minutes to go hear about it. It's really, really good, and I want to be clear that the following is not a critique of the game or some indictment against it, but simply an explanation of why it doesn't fall under the umbrella of Palette RPG.

Lancer is a game that is primarily built around its intricate tactical combat system. That doesn't mean it doesn't have other selling points: The universe has some cool and unique sci-fi in a setting that is positive and hopeful, yet still leaves room for conflict, drama and tension; the out-of-combat RPG elements are lightweight and minimal for maximum flexibility (though later expansions have provided much more involved alternatives); and the general aesthetic is drop-dead gorgeous, creating a look unlike any other Giant Robot Thing out there. I'm actually running a Lancer campaign at the time of writing, and I'm having a really good time with it.

If you read the book, you will see that the two biggest chunks are the rules for the tactical mecha combat, followed by a staggering shopping list of pilot talents, equipment, mechs and mech components, all for the purpose of creating your very own cool mech build. The GM side of the book is also thick with options, providing a huge selection of NPC classes, tons of optional features to customize and complicate those base classes, and a solid dusting of advice on creating fun, balanced and/or challenging battles for your players. There are also several expansion books of various size, which introduce even more lists of stuff for both sides of the table, on top of optional non-combat rules and setting tidbits.

|

| I cannot overstate the quality of the art in this book. |

The game also has a big, lovely community, which has created tons of additional material for the game, publishing dozens (if not hundreds) of new player mechs, components, talents, combat scenario setups, NPC classes, and more; the sheer amount of fan-made options dwarfing the total fan output of many, much older and more popular games. With the built-in ability to mix and match these various game elements, you're unlikely to ever run out of new stuff to see, new combinations to make and new enemies to fight. Lancer is very much a "can be customized" game, impressively so.

So, why is it not a palette game?

Like I said, the game is built around the tactical combat. Everything in the book feeds into it one way or another: the non-combat portions of the game serve primarily to efficiently advance the plot and get you into position for the next fight, and the grand majority of fan materials are more options for the build-a-mech-for-fightin' side of things. The mech battling system is the irremovable, unalterable core of the game. Without the combat system, there is no Lancer, and so everything else orbits around that component. This has three effects, the first of which is that straying from the combat rules becomes very, very hard.

You could make changes. If you really really want to, you absolutely can decide that Impairment no longer slows, or that Soft and Hard Cover does more than providing 1 or 2 Difficulty to attacks, respectively. But any changes you make to it can have a dramatic ripple effect throughout the entire system: messing with, say, cover, means that you're altering the basic assumptions of the game, impacting any feats and mech components that interact with the cover rules, and potentially breaking an untold amount of other interactions. All of the game systems that are customizable firmly rely on a collective agreement that the underlying rules are set in stone, because otherwise my build for a tricked-out ninja frame with cover-generating shuriken cloaks suddenly doesn't work anymore (or, works too well). So generally speaking, the entirety of the combat system is not to be reinterpreted.

The resulting second effect is that making any in-the-moment rulings or GM calls becomes less "fair". As a game becomes more intentional and rigid in its design, the GM's role as an arbiter of reality becomes replaced with something closer to a traditional Referee, primarily serving to keep players on track, make sure the rules are adhered to, to keep hidden information hidden while it impacts play; only occasionally making calls when the rules aren't 100% clear on something. The GM deciding to stray from the combat rules because they seem inappropriate for a situation becomes less acceptable, since so much of the players' previous decisions have been made under the assumption that the written rules are absolute law. The system is the primary engine through which players interpret reality, with the fiction acting as the "thematic" layer over the mechanics. The door is always open to "rule of cool" moments, where you decide that, yeah, Steve's mech can actually do a zipline jump using his mech's pulley system, but even kind of thing is almost universally reserved to strictly out-of-combat "narrative" use.

|

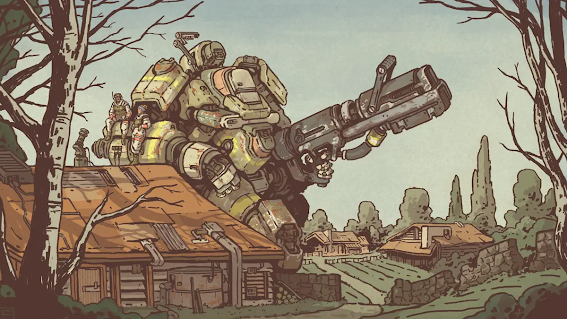

| Your mech is absolutely part of the "narrative world", and that's important to remember. |

The third effect, arguably the most dramatic one, is that the combination of high combat complexity and expectation of regular combat mean that the game must, by nature, rely more on predetermined narrative outcomes. Scenarios are essentially impossible to make up on the spot for non-veteran GMs, since a typical fight requires a setup and stakes, a battle map, one or more objectives, clear definitions for any special rules in play, and a fully fleshed out enemy force consisting of at least 3 different enemy classes, each of which have a dense stat block and handful of highly specific abilities. And ideally, you want all of that to actually be good - you want the scenario to have dramatic impact, you want the enemy composition and map to create an interesting tactical challenge that gives your players a chance to flex their tools and find creative solutions, and so on. So yes, you want to prepare your fights ahead of time.

And that means that, before your next game night, you need to have at least partially prepared your next fight. Which means that, ultimately, you need to direct the PCs towards the fight you have prepared. And while this structure isn't necessarily a bad thing, it does mean that spontaneity is always going to be limited; tweaks can always be made on the fly ("Whoops, they killed the enemy lieutenant before the fight started; I guess they successfully made the next fight easier for themselves"), and sometimes they might even completely bypass a fight ("Whoops, they figured out a bulletproof way to resolve this situation without the encounter ever happening. Good for them!"). These are great moments, as player creativity and investment should be rewarded; but it can't happen too much, because we are still here primarily to play the Tactical Mech Combat Simulator Game.

Now, there's absolutely ways you can lessen the impact of this linearity: you might go through the effort of preparing several potential combat scenarios in advance, or make broad easily-tailored scenarios that can be pulled out at any time, or create a situation where a set of pre-prepared fights can happen in any order; or, if your players are cool with it, you can agree to end the session when a fight is about to start, and then immediately begin the next game night with the combat. This is not an exhaustive list, and for many, the prep isn't that much of a hassle. But all of these still accept the basic premise that, one way or another, there will be a series of combat encounters, for each of which we will enter Combat Mode, and which we will play out adhering pretty strictly to the rules for Combat Mode.

And this is what excludes Lancer from being a Palette game. Which, I want to emphasize one more time, is not a bad thing, or failing of the game! It never tried to be one. Lancer is absolutely a game about a specific thing, and does its damndest to provide you with a good system and reliable framework to do some really cool stuff within that space.

And before anyone points it out: Yes, I know Lancer is deliberately modal, and has a non-mech-combat "story" mode , which is much more free-flowing, reliant on fiction and collaborative storytelling, and much more open to rulings and and calls based on the fiction. And that's true, but I'd say that

a) The system falls too far on the opposite end of my definition, since it barely even provides a baseline of rules to use in the first place and relies completely on GM whims to move things along (to the next combat);

b) It is not a stand-alone game, but a subsystem meant to provide light mechanical tension during the dramatic moments leading up to the next fight, which means it's still a guiding framework more than anything else; and the book itself says it was designed to be as minimal, unobtrusive and fast-moving as possible, because

c) Literally nobody got into Lancer for the narrative mode between combats. Come on.

|

| Do you have any idea how ridiculous you sound? |

I could have used many other major modern RPGs as an example here, but Lancer fulfils my dual purpose of wanting to use a game that's not immediately clear cut so I can delve into it, and also wanting to talk about how cool Lancer is. I could have, for example, instead talked about Blades in the Dark, as a "light" game that strives to have a mechanical implementation and guided, modal play for everything a GM that might normally arbitrate themselves. Or I could have used Technoir, as a game that utterly relies on everything feeding into, and from, its neato conspiracy web system, without which the entire game falls apart. You get the point.

Now, you'll all agree that this was just an excellent, well-worded and very useful example of what a Palette RPG isn't. So now comes the obvious follow-up,

What is?

I won't go into as much excruciating detail for the individual games of the "is" pile. Instead, I'll give a quick rundown of a few examples and the major points.

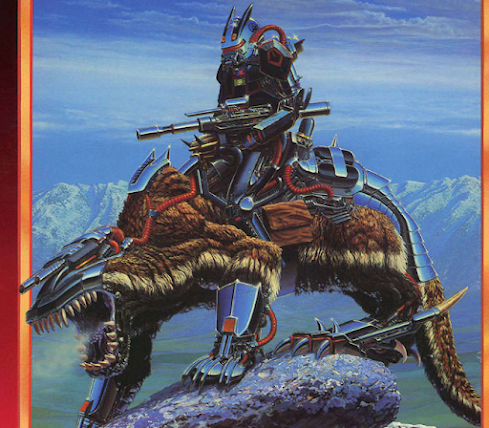

|

| You absolutely saw this one coming. |

Perhaps the most obvious one, and most relevant to this blog, are "OSR"-ish games, both old and new. Things like pre-3.X You-Know-What, Gamma World, Classic Traveller, and the like. These games are prime examples of what I'm talking about: a book that gives you a minimal amount of character definition, serving in equal parts as mechanical elements and inspiration for in-game concepts; a collection of mechanics and protocols that, while robust and flexible, are also easily omitted when not of use to the game; and a smattering of GM tools and advice that serve primarily to direct the GM's thought process towards emulating an interesting world, rather than acting as the hard-coded physics within a more universal and mechanical system.

For something more recent and modern, I'd cite the excellent FIST, the cold war paranormal mercenary RPG, as a prime example. Built entirely around the assumption that the GM can be trusted to carry the fictional world on their shoulders, the entirety of the player-facing system lies on the first 10 pages (of which 4 aren't example characters, player advice, or an example of play) of the 150 page book; and the remaining wordcount is a dense collection of overall solid GM advice, tips and tricks, as well as some basic tools for setting up a game.

The remaining 4/5ths of the book are just a massive array of tables, optional systems that include suggested implementation, and just a bunch of wonderful toys for you to make your very own ridiculous blend of Metal Gear and the A-Team. The fact that the book is mostly GM-facing muddies the Palette definition a little, since that means there are few immediately obvious rules for players to base their assumptions of the universe on; but I'd argue that between the Traits, the Roles and the simple-but-functional core system that still gets a basic idea of the genre being emulated across, it fits the bill. And, before you say it, I know what you're thinking: "Hey, that sounds like a toolbox game!" And under one of the given definitions, you'd be right! Turns out a game can be both, and that Toolbox (whatever that is) and Palette aren't exclusive! Funny, that.

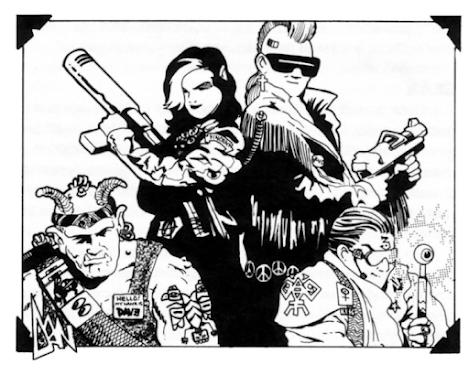

Finally, for a "harder" example, I'd use the second edition of Shadowrun. No, really.

|

| I'll wait for the derisive laughter from the back to stop before continuing. |

The franchise is infamously crunchy, and has a lot of moving pieces, but I would argue that SR (2e, at least) absolutely falls under my definition. While the game is inarguably dense, especially once you start moving into the expansion books, I also believe that the game is very open to GM ruling overtaking rules, and intentionally so. The fundamental elements of the basic character creation and the core combat are fairly open and easy to tweak in various ways without shattering everything (though admittedly much less so than something like the other games I've mentioned), and can easily have the individual functions moved around, repurposed or ignored as the dramatic requirements dictate.

Similarly, the game's individual subsystems such as magic, decking or vehicle rules can get somewhat complex. However, and this is important, they only become as complex as you decide to let them become. The system does not break down if you decide to downplay the impact of dumpshock, or fail to follow the letter of the law on how to determine the exact drain TN for the fireball you just flung at a group of Lone Star goons. While some of what I said in regard to Lancer can absolutely apply here as well, Shadowrun differs because a greater majority of its mechanical outcomes are fictional as well as mechanical, in every area of play. For example, some spells do simply Deal Damage and leave it at that, but some might also start fires, or telekinetically manipulate objects, or alter someone's mental state - the outcomes of which are entirely within the GM's purview. How does levitating someone actually impair them? You tell me! Does every battle have to be to the death? Of course not, decide that on a fight-by-fight basis! How tough is the security on this run? No clue, here's a very broad guideline but you figure out the details yourself. How does car combat work? Here's like 3 pages of loosely defined mechanical impact, you decide how much you want to complicate it beyond that!

I also believe that whether something is a Palette RPG is majorly influenced by designer intent, and I think that SR2e absolutely provides evidence of that intent. Throughout the core book, the text not only discusses the gameplay implications of the various mechanics, but also how one might modify them or reinterpret them as the situation calls for. In fact, there's one section that is very explicit about this, going so far as to say that there are times when the rules should absolutely be ignored or simplified. The example provided is that, if the party's Decker is doing matrix footwork to gather information before a run, that it would be entirely too much for the GM to create an entire matrix network for the decker to play through while everyone's sitting around with their thumb up their nose; and instead, the GM should simply call for a single Computer Skill roll to determine how well the Decker does, and tell them what the legwork turned up. While this is the most explicit example, the entire book permeates the same air of "use the rules when you need them, not whenever they might be useful"; which is one of the main reasons I love it so.

Now I know I'm probably losing some of you with this last example, and I have no doubt that some of you could use my own example to explain why my definition doesn't fit the shoe for any of the above. Again, I bring up SR2e as an example because I consider it an edge case and think that it's worth discussing, and because I really want to talk about SR2e (which I might be doing a lot in the near future, hint hint).

|

| Pose as a team, because shit might just become real. |

What was the point of this, exactly?

I want people to be able to talk more fruitfully about the games they play. In a hobby that is entirely about ideas, having clear and understandable language to convey those ideas is crucial. And while I myself am just... obviously terrible at conveying any ideas in a succinct way, I do believe that we can only stand to benefit by looking for new methods to avoid miscommunication and gain a better understanding of what we, and others, enjoy in our games.

Personally, I love Palette RPGs. The contrast with very literal "rules as mechanics of the game universe" gameplay means that players can involve themselves more in the fictional side of things, thinking about how their characters perceive things in-universe, and consequently trying to solve problems by using in-universe logic which is then, ideally, backed up and emulated by the game system. But game systems are inherently limited, as it is impossible for a book or ruleset to provide meaningfully useful answers to every possible question or situation that might come up during play. And those moments are why we have a living, breathing GM, capable of interpreting a piece of fiction and using a shared logic and understanding of that fiction to decide what the "correct" thing to happen in that moment is.

The GM is not a perfect machine, of course. They can make mistakes, be inconsistent, and occasionally even be flat-out wrong; this is an inherent risk of doing anything creative with other people, and why it's not always easy to fully trust someone else to be a fair and just arbiter of reality. This is why many people very much don't enjoy Palette RPGs, instead preferring systems that are much more codified and try to provide hard answers to questions that might crop up. And they're not wrong to do so! But I believe that the inherent magic of the roleplaying game lies in that invisible space between the rules and your imagination, the microcosm of suspended disbelief that only comes from us agreeing that we're playing a game with rules, but also that those rules are there to help us when we need them, not to guide or constrain us.

The Palette RPG is a book of rules, not a rulebook - a guide to helping you create something together, that is both play and fiction at the same time. The rules exist to help enable the solving of interesting questions when they fictionally crop up, not to inform when those questions should appear and how they should be seen.

Hopefully, there'll be a day when I see someone in the wild say "I like this Palette RPG!". And I'll be happy, because I know what they mean, and that there's someone out there who enjoys the same parts of this hobby that I do.

Or, they'll be wrong, and I can correct them; because I coined the phrase, which means that I get to decide if they're using right or not. That's how language works, right?

No comments:

Post a Comment